May Tyrants Tremble: William Drennan and the politics of dissent

This weekend marks the anniversary of one of the more improbable incidents in Ireland’s strange and troubled past.

On 7 June 1798 Dixon’s Inn in Ballymena became the headquarters of a Republic, ruled over by a Committee of Public Safety in the French tradition. Sentries were posted around all the surrounding roads and throughout that night armed men paraded the streets blowing trumpets and conch shells. A green flag flew from the church steeple.

The following afternoon fugitives from the United Irishman’s crushing defeat at Antrim started to straggle into the town and, overnight, what had been an army of 10,000 melted away. Ballymena had been the seat of revolutionary government for two days.

The 18th Century is bookmarked by two brutal conflicts which set the course of Irish history: the Williamite War which asserted the Protestant Ascendancy, leaving 100,000 dead and the Rebellion of 1798 (up to 50,000 dead) which precipitated the Act of Union with Britain in 1800.

Sandwiched between them was a climate change catastrophe, the Great Frost of 1740 and subsequent famine which killed up to 450,000 – a quarter of the population. The Year of Slaughter was the last and most devastating severe weather event of the Little Ice Age. Our ancestors were no strangers to death.

Much has been written about these terrible wars, the famine is largely forgotten. But the rest of this intriguing period is as much a war of ideas as it is about pitched battle and atrocities. And what emerged from it laid the foundations of modern European life.

This was the century of the Enlightenment, a movement which upheld individual judgement against the censorship of church and state. The German philosopher Immanuel Kant described it as a coming of age of mankind, a release from childhood superstition and inherited prejudice.

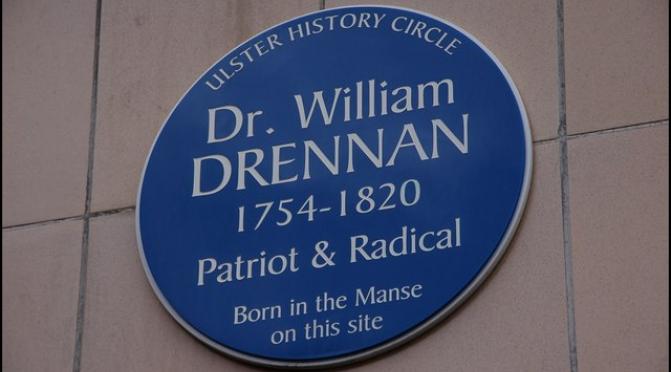

One of its most intriguing proponents in Ireland was Dr William Drennan who is the subject of a new biography May Tyrants Tremble by Fergus Whelan, just published by the Irish Academic Press.

Drennan took no part in the 1798 insurgency. He was not executed. Indeed he all but disappeared from public life after his acquittal in a trial for seditious libel in 1794. He was socially awkward and suffered from ill-health for most of his life. His weapon was the pen, not the sword. But he became the United Irishmen’s foremost propagandist and his brilliant writings, mostly written in letter form illuminated the build up to the conflict.

Drennan’s convictions spring from his Unitarianism, which was illegal until 1813. Unitarians reject the doctrine of the Trinity, believing Christ to be a man. Drennan described him as an “unlettered prophet” . He had no truck with church hierarchies: “I believe the priesthood in all ages has been the curse of Christianity and I believe that there will never be happiness or virtue on the face of the earth until that order of man be abolished and until there is a greater equality of property which may deliver the rich and the poor from the vices inherent to their condition.”

Crucially he believed that “There is no earthly authority in religious matters and no man should suffer penalties for his religious opinions.”

Drennan went on to write the oath, or test, that the United Irishmen were required to swear before joining the movement: ““I shall do whatever in my power to forward a brotherhood of affection an identity of interests a communion of rights and a union of power among Irishmen of every religious persuasion …”

In this context it is important to remember that there were three factions in Ireland at that time, not two. Ascendancy Ireland that controlled Dublin Castle and the government and was predominantly Anglican, the Catholics, who accounted for 80% of the population and an increasingly wealthy Dissenting community whose power-base was in the north.

Dissenters were also subject to discrimination. Until 1780 they were subject to the Test Act of 1708 which stated that the taking of Anglican communion was a pre-requisite for public office. This was regarded as a “Badge of Slavery.”

Drennan was one of those who would raise a glass to the executioners of Charles I (a martyr in the Anglican tradition) on 30 January every year. As a young man he told his sister he wished “all the tyrants in Europe had but one neck, that one neck laid on the block …”

He was also an admirer of King William of Orange who he saw as a man of “stern integrity” and “unshaken fidelity”.

Drennan attended the Strand Street Unitarian congregation when he lived in Dublin, a church with links to the Cromwellian invasion of Ireland the previous century. The secret society he and other members of the congregation founded was referred to as the “king killers of Pill Lane.”

In Ireland, just as in England’s civil war the previous century radical religious beliefs fused with radical political views to fuel revolution.

However, how does that explain Drennan’s support for Catholic emancipation and making common cause with Catholics to overthrow the state?

After all throughout this period the Catholic church was closely associated with authoritarianism, intolerance and the Ancien Regime.

The fact that regime change would not be possible without them was one compelling factor. But to Drennan and those like him there was another reason too. At the time Europe was a continent of confessional states. Religious conflict was deeply destabilising and the coercion of religious dissenters was the norm. Religious toleration was a pejorative term for most and religious leaders used the words of Christ quoted in Luke 14:23 “Compel them to come in” as the justification for often brutal suppression.

Yet because Drennan was one of those who believed that there was no earthly authority in religious matters religious suppression was unjustifiable.

This is not to say he did not have misgivings about emancipation. In one of his publications he wrote: “the Catholics of this day are absolutely incapable of making a good use of political liberty.”

What seemed to be the key for him was universal education. Presumably in his mind this would liberate them from superstition. The Ireland that the United Irishmen seemed to envisage was anti clerical, enlightened and cosmopolitan – a rather different vision from the state that ultimately emerged in the 1920s.

Whelan devotes a section of his book to defending charges that Drennan was an anti-Catholic bigot. The charge is based on a remark made in a private letter to a friend about how bored he was living in Newry: “There is nothing stirring here but pigs and papists …” Whelan argues that this remark was directed at the wealthy Catholics in the town who shunned his medical practice, disapproving of his radical ideas. Indeed he struggled financially both in Newry and Dublin, finding it hard to balance his revolutionary activity with holding a respectable position as a doctor.

Much of this meticulously researched and highly enjoyable book is based on a very precious archive – the letters he wrote to and received from his sister Martha. These notes do more than shed light on the underground world of radical thought, they also give remarkable insights into 18th Century (middle class) life. More too they offer tantalising glimpses of a neglected topic – the role of women in 18th Century Ireland. Martha is Drennan’s chief coach and critic who both guided and goaded him into producing his best work.

In later life Drennan helped set up the Belfast Academical Institution in his home town of Belfast.

His last known letter to his sister was sent in 1819 shortly after the Peterloo Massacre. He wrote: “It is this contempt for the populace that will be the ruin of the gentry.”

He died the following February and his coffin was carried to its resting place by six Catholics and six Protestants.

Drennan was not involved in the rising and many of his views were not representative of the time, or even many of those who did take part. Yet much of what he stood for came to pass, eventually: religious toleration; Catholic emancipation; universal suffrage; human rights; universal education. His dream of a brotherhood of affection in Ireland still awaits.

May Tyrants Tremble by Fergus Whelan is published by the Irish Academic Press.

Share Article...

Join the Conversation...

We'd love to know your thoughts on this article.

Join us on Twitter and join the conversation today.

Join Our Newsletter

Get the latest edition of ScopeNI delivered to your inbox.

One final article – a goodbye

One final article – a goodbye A story to inspire ...

A story to inspire ...  The shameful waste of our money

The shameful waste of our money  Fund's new strategy unveiled

Fund's new strategy unveiled The true cost of deprivation and division

The true cost of deprivation and division  An ancient key to longevity

An ancient key to longevity